Multilateral health organisations such as the World Health Organisation (WHO), U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have long been cornerstones of global health, driving programmes that have significantly improved health outcomes worldwide. However, these agencies are now navigating unprecedented financial challenges as traditional high-income donors sharply reduce their aid contributions. This shift disrupts essential health services and forces multilateral health bodies to adapt rapidly to an uncertain economic landscape.

Historically, these organisations have been predominantly funded by foreign aid from advanced economies, which has recently seen substantial cuts. By mid-2025, announced reductions in official development assistance (ODA) from major donors — including Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the US — totalled a 15–22% decline compared to 2023 levels, equivalent to US$41–60 billion reductions. High-income governments cite post-pandemic fiscal pressures, inflation, geopolitical crises, and shifting domestic political attitudes as reasons for the cutbacks. For instance, the UK broke its 0.7% GNI aid pledge, aiming to further lower it to 0.3% by 2027, reflecting a waning political appetite for sustained global health aid.

The repercussions are severe and immediate. WHO faces its greatest financial disruption in memory, exacerbated by the US withdrawal that once constituted nearly 20% of the WHO’s budget. The organisation has been forced to slash its two-year budget by 21%, significantly impacting its ability to respond to health emergencies and maintain basic health systems, risking a US$600 million shortfall this year alone. Programmes critical to global health, such as pandemic preparedness and polio eradication, are under threat, with country offices closing and recruitment frozen.

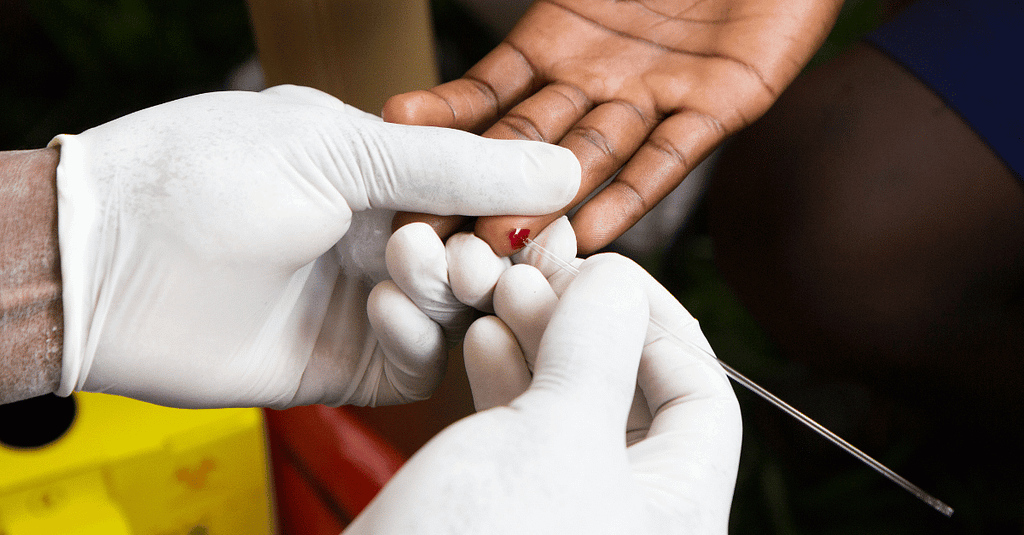

Similarly, UNAIDS confronts a catastrophic 40% budget cut following the US decision to halt funding, particularly from PEPFAR. This could lead to six million new HIV infections and four million additional AIDS-related deaths by 2029, according to UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima. The agency is drastically reducing staff from 608 to 280 and closing half its country offices, severely impacting HIV prevention and treatment programmes.

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, is experiencing comparable challenges. At its June 2025 pledging conference, Gavi secured just over US$9 billion, falling short of the US$11.9 billion needed for its 2026–2030 immunisation goals. Notably, the US, a previous major contributor, refused to pledge funds, severely limiting Gavi’s ambition to vaccinate 500 million additional children by 2030. Consequently, some regions’ childhood vaccination rates have stagnated or declined, driven partly by misinformation and lower funding.

UNICEF also faces significant setbacks, forecasting a 20% income reduction by 2026 compared to 2024. The agency warns this could deny nutrition support to nearly 15 million children and mothers, drastically increasing severe malnutrition and child mortality risks. Emergency programmes face cuts of 30–50%, potentially leading to preventable deaths from malnutrition, inadequate sanitation, and lack of essential health services.

In response, these organisations are undergoing rapid adaptation. The WHO has successfully advocated for a 20% increase in mandatory member contributions by 2026, aiming for greater funding stability. It has established the WHO Foundation to attract philanthropic donations and hosted investment rounds to secure multi-year commitments. Internally, WHO is streamlining operations, prioritising impactful programmes, and exploring innovative financing options, such as a proposed US$50 billion endowment fund.

UNAIDS is similarly restructuring, cutting its workforce significantly and contemplating integration within WHO to ensure sustainability. Strategic advocacy and integrated health approaches are being emphasised to maintain essential HIV/AIDS services despite funding challenges.

Gavi and UNICEF are diversifying funding through increased private sector partnerships and innovative financing models. Gavi secured new commitments from emerging donors like Indonesia and Uganda and substantial support from development banks offering affordable loans. UNICEF is leveraging private donations and individual contributions to offset governmental funding shortfalls.

Emerging donors such as China and Gulf states are becoming significant contributors, reshaping global health funding dynamics. China pledged an additional US$500 million to the WHO, positioning itself prominently amid Western aid cuts. Gulf countries collectively pledged significant funds to global health initiatives, highlighting the changing geopolitics of global health financing.

Philanthropic foundations, notably the Gates Foundation, continue to play vital roles, pledging US$1.6 billion to Gavi and substantial contributions to WHO’s emergency financing. Such partnerships introduce innovation and efficiency but raise governance and accountability concerns due to increased reliance on non-governmental sources.

The evolving financial landscape poses significant risks to health equity, particularly affecting marginalised groups reliant on sustained donor support. There is also a geopolitical risk of fragmented global health approaches, as emerging donors may prioritise bilateral funding, potentially undermining multilateral cooperation.

However, these challenges present opportunities for reform and innovation. Multilateral agencies must enhance efficiency, explore sustainable domestic financing mechanisms, and build resilience against future funding volatility. Innovative financing strategies, such as pandemic bonds, social impact investments, and new South-South partnerships, could help create a more diversified, resilient global health funding model.

Sustaining the achievements of global health organisations amid declining traditional aid requires urgent, collective action from governments, emerging donors, philanthropies, and the private sector. Protecting health advances demands renewed global solidarity, smarter investments, and coordinated efforts to ensure these agencies continue their essential roles in safeguarding global health.

Multilateral Health Organisations Adapt to Shrinking Aid from Traditional Donors was originally published in BeingWell on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.